Global demographic revolution and the future of humanity

Math modeling

Thomas Malthus was the first to turn to mathematical modeling to explain the limitation of population growth 200 years ago. In his model, exponential population growth, which doubles over time, is limited by linearly increasing food production, i.e. it is defined by resource depletion and starvation. These ideas captured the minds for many years and were developed already in the twentieth century, in the global models of the Club of Rome, created with the help of powerful computers and extensive databases. The research conducted led to an understanding of the significance of global problems, but the conclusions of the Limits to Growth project about an imminent resource crisis turned out to be incorrect. As the American economist and Nobel Prize winner Herbert Simon noted: “Forty years of experience in modeling complex systems on computers, which became more powerful and faster every year, have shown that brute force does not lead us along the royal path to understanding such systems... To overcome the “curse” complexity," modeling must return to its original principles."

The scale of the task itself, which has fundamental meaning for the sciences of man and society and practical significance for politics and economics, forces us to look for new ways to study this most important problem. The development of the population of our planet should be considered as the evolution of a self-organizing system, based on the ideas of synergetics. It is the methods of complex systems science that provide this opportunity and can introduce new concepts into traditional humanities fields. To do this, first of all, it is necessary to determine the law of growth and the nature of the demographic transition, which leads to the limitation of explosive growth and stabilization of the Earth's population, which has become the most characteristic feature of the current stage of the world demographic process.

The world as a global system

Modern development cannot be understood without considering the entire history of mankind, starting from the very first steps of its origin and evolution. The key should be considered the study of the evolution of the human system and those interactions that control growth. It is the interconnectedness and interdependence in the modern world, caused by transport and trade connections, migration and information flows, that unite all people into a single whole and allow us to consider the world as a global system. However, to what extent is this approach valid for the past? Due to the compression of historical time, the past turns out to be much closer to us than it seems at first glance. Within the framework of the proposed model, it is possible to formulate criteria for systematic growth, and as in the very distant past, when there were few people and the world was largely divided, the population of individual regions and countries slowly but surely interacted. However, in relation to the Earth's population as a closed system, migration should not be taken into account, since on a planetary scale there is nowhere to emigrate yet.

It is also significant that biologically all people belong to the same species, Homo sapiens: we have the same number of chromosomes - 46, different from all other primates, and all races are capable of mixing and social exchange. The habitat of our population is almost all suitable areas of the Earth. However, in terms of our numbers, we exceed the number of living beings comparable to us in size and method of nutrition by five orders of magnitude - a hundred thousand times! Only domestic animals living near humans are not limited in number, unlike their wild relatives, each species of which occupies its own ecological niche. There is every reason to assert that over the last hundred thousand years man has changed little biologically. But at a certain stage, as a result of the Neolithic revolution, humanity separated from the rest of the biosphere and created its own environment.

The main development and self-organization of our population took place in the social sphere. This was made possible thanks to a highly developed brain and consciousness - what distinguishes us from animals. Now that human activity has acquired a planetary scale, the question of our interaction with the surrounding nature has become increasingly urgent. Therefore, it is important to understand what factors determine the growth in the number of people on our planet. To do this, in accordance with the methods of synergetics, we will choose the population of the entire Earth as the main variable.

How many of us are there?

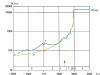

The population of the world at time T can be characterized by the total number of people N - the leading variable subordinating all others. The asymptotic method of synergetics allows us to neglect all other factors influencing growth at the first stage of analysis. The growth process will be considered on average and over a significant time interval - over a large number of generations. Then the life expectancy of a person will not be explicitly included in the calculation, as well as the distribution of people in space and by age and gender. This excludes exponential and logistic growth, which have a constant internal scale - doubling time. Demographic data makes it possible to describe the growth of the world population (see Fig. 1) by a power law, where time T expressed in years AD

Billions

A number of authors have proposed it as an empirical formula, since it characterizes the growth of the Earth's population over many thousands of years with amazing accuracy. However, we will consider this expression as a description of the process of self-similar development, which is represented by the population explosion. In other words, with self-similar growth, the dynamics of the process remain unchanged. Such growth, following the hyperbolic law, is known in physics and synergetics as exacerbation mode.

Figure 1. World population from 2000 BC. until 3000. Population growth limit N∞ = 10-12 billion.

1 - world population from 2000 BC. according to Biraben.

2 - Hyperbolic growth and exacerbation regime characterizing the demographic explosion

3 - demographic transition

4 - population stabilization

5 - Ancient world

6 - Middle Ages

7 - New and 8 - Recent history

- plague of 1348

O- 2000

↔ - error

On a semi-logarithmic grid, exponential growth is depicted as a straight line, which cannot in any way describe the development of humanity over any significant period of time. The growth graph clearly shows the compression of historical time as we approach the demographic transition.

A factor that is not included in the growth formula is the length of the reproductive period of a person's life. But it is precisely this that manifests itself during the passage through the demographic transition and limits the scope of application of the asymptotic growth formula. Taking this circumstance into account allows us to get rid of the divergence of growth as we approach 2025, as well as a similar feature in the distant past.

In the statistical theory we propose, the main dynamic characteristic of the system becomes the dimensionless constant K = 62000. This large parameter determines all the relationships in the calculation results and is also the scale of the size of the group of people involved in the collective interaction that describes growth. Numbers of this order characterize the optimal scale of a city or metropolitan area, and in population genetics, the number of a sustainably living species. Thus, the initial population of our distant ancestors in West Africa was about 100 thousand (K ~ 10 5). Thus, the value of K is associated with a number of phenomena in which the cooperative properties of a person are manifested; therefore, the growth rate in the era of explosive development can be represented in the form of a basic equation, where t=T/τ is time measured in units of effective generation, where τ= 45

In this nonlinear equation, growth rate is equated to collective interaction, which phenomenologically and averagely describes all processes of an economic, technological, cultural, social and biological nature. In other words, the growth rate depends entirely on the state of the system at a given moment and is equal to the square of the world population, which gives a measure of the network complexity of the demographic system. In many-particle physics, the well-known collective interaction is described in the same way, such as the van der Waals interaction in the theory of gases.

According to the above formula, the growth rate is expressed in terms of the world population at a given point in time. However, this expression can be interpreted as an average interaction associated with all previously accumulated information.

You can easily calculate the limit to which the human population tends in the foreseeable future after the demographic transition ![]() billion and express through time τ and population world billion. in T1=2000 the beginning of growth

billion and express through time τ and population world billion. in T1=2000 the beginning of growth ![]() million years ago. If we integrate the entire process of growth from T 0 to our time T 1, then we can estimate the total number of people who have ever lived on Earth and is equal to

million years ago. If we integrate the entire process of growth from T 0 to our time T 1, then we can estimate the total number of people who have ever lived on Earth and is equal to ![]() billion people The justification and conclusion of all calculations are given in the author’s monograph “The General Theory of the Growth of the Earth’s Population”.

billion people The justification and conclusion of all calculations are given in the author’s monograph “The General Theory of the Growth of the Earth’s Population”.

The mathematical apparatus used in the model is extremely simple and would have been quite accessible to Malthus himself, who, although he was planning to become a priest, took 9th place in a mathematics competition at the University of Cambridge. However, the application of the model to describe the development of society requires a revision of the traditions and approaches rooted in demography. Understanding the theory requires a certain effort on the part of those who are little familiar with the general methods developed in theoretical physics and the proposed approach, which to some may seem abstract and formal. This is due to the need to abandon reductionism - the desire to present everything as the result of the action of elementary factors and direct cause-and-effect relationships. Paradoxically, in this case it turns out that growth asymptotically depends not on fertility, but on the difference between fertility and mortality, which is directly related to socio-economic conditions. It is the interdependence and nonlinearity of strongly coupled mechanisms that makes us look for systemic (integrative) principles to describe the behavior of a complex system over long periods of time and over the entire space of the globe.

The effective interaction that determines growth is realized throughout the entire population of the Earth and over a significant period of time. Therefore, the overall nonlinear law of growth is neither reversible nor additive; it cannot be applied to a single country or region, but only to the entire interconnected population of our planet. But the global law of growth affects the demographic process in each country.

Global connections

Collective interaction is based on the transfer and multiplication of generalized information, which is associated with the activity of the human brain and mind. The dissemination and transmission of information (technology, cultural and religious customs, scientific knowledge, etc.) through an irreversible chain reaction qualitatively distinguishes both an individual and all of humanity in its development.

A person has a long childhood. The process of mastering speech, upbringing, training and education stretches for 20 or even 30 years. These years are used to form the mind, personality and consciousness, but childbearing is significantly delayed. This is the only way of development peculiar only to people, leading to the organization and self-organization of society.

The mechanism of cultural inheritance qualitatively distinguishes social inheritance in humans from genetic inheritance in the rest of the animal world. If biological evolution according to Darwin occurs without the inheritance of acquired characteristics, then social evolution rather follows Lamarck's idea of their transmission. This is how collective experience, proportional to the information interaction of all people, is transmitted to the next generation and spreads in breadth, synchronizing the development of humanity on our planet. The commonality of the global historical process has been repeatedly emphasized by outstanding historians Fernand Braudel, Karl Jaspers, and Nikolai Conrad.

During the Stone Age, humanity spread throughout the globe, with up to five glaciations occurring during the Pleistocene, and sea levels changing by hundreds of meters. At the same time, the geography of the Earth was redrawn, continents and islands were connected and separated again. Man, driven by cataclysms, explored more and more new lands, and his numbers grew at first slowly, then with an ever-increasing speed. It follows from the concept of the model that in cases where a population found itself separated from the bulk of humanity for a long time, its development slowed down. This is the fate of the Western Hemisphere, isolated 40 thousand years ago. Systematic growth took place in the Eurasian space, through which tribes roamed and peoples migrated, ethnic groups and languages were formed. Trade connections played a significant role, and the greatest importance was the Great Silk Road, a network of caravan routes connecting China and Europe, as well as India. Along this path, starting from antiquity, there was intense intercontinental exchange, technology and culture spread. Throughout the entire ecumene, the commonality of the world’s languages serves as significant indicators of interactions and migrations. Global connections are indicated by the emergence of shamanism and its spread a hundred thousand years ago, and from the “Axial Time” by world religions.

Demographic transition

Data on the world's population over the entire range of times fit the proposed model with sufficient reliability, despite the fact that the further we go into the past, the less accurate the data we have. Let us note that we know the time of historical eras of the past much more precisely than the size of the world population, for which only the order of magnitude is determined (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Of interest are future population calculations in which the modeling results can be compared with data from the UN and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA). The UN forecast is based on a compilation of a range of possible fertility and mortality rates for nine regions of the world and is extended to 2150. According to the UN's optimal scenario, the world's population by this date will reach a permanent limit of 11,600 million. According to a 2003 report by the UN Population Division, by 2300 the planet's population will average 9 billion. The results of demographers' calculations and the mathematical model lead to the conclusion that after the transition, the Earth's population will stabilize at 10-11 billion people.

The duration of the transition, during which the Earth's population will triple, takes only 2 = 90 years, but during this time, which is 1/50,000 of the entire history of mankind, a radical change in the nature of its development will occur. However, despite the shortness of the transition, this time will survive 1/10 of all people who have ever lived on Earth. The severity of the global transition fully depends on the synchronization of development processes and interaction that takes place in the world demographic system. This serves as an undeniable example globalization, as a process that covers the entire population of our planet. However, the model indicates that humanity has always, from the very beginning, grown and developed as a global system, where effective interaction, common in nature, is realized in a single information space.

Figure 2. Demographic transition 1750-2100

World population growth averaged over decades. 1- developed countries; 2 - developing countries

"The connection of times has broken down..."

At present, it is the shock, the aggravation of the transition (when its characteristic time - 45 years - turns out to be less than the average life expectancy - 70 years) that leads to a disruption in the growth developed over millennia of our history. Today it is customary to say that the connection between times has been broken. This is due to unbalanced growth, leading to unsettled life and the stresses characteristic of our time. Associated with this process is the crisis and collapse of social consciousness, starting with the management of empires and countries, and ending with the level of consciousness of the individual and family. Associated with the breakdown of social governance is the rise of organized crime and corruption. It is possible that the spread of terrorism was also a consequence of the disruption of global balance. Unsettledness and lack of time to take root of what is fixed in the field of culture by tradition are undoubtedly reflected in the disintegration of morality, in the art and ideologies of our era. Thus, in the search for new ideas, when there is no time for their formation and dissemination, sometimes there is a rollback to the once fundamental ideas of the past. At the same time, new structures, such as the European Union, TNCs or non-governmental organizations, are looking for new ways of self-organization of society. Powerful global information systems such as the Internet are emerging, which materialize the collective consciousness of humanity. An international system of media and education is taking shape. Science has always developed in a single world of knowledge.

If reason and consciousness led to an exceptional, explosive growth in the number of people on Earth, now, as a result of a global limitation of the main mechanism of information development, the growth suddenly stopped, and its parameters, which fundamentally affect all aspects of our lives, have changed. In other words, as in the world of computers, our “software” does not keep up in its development with technology, with the “hardware” of civilization.

Unevenness of historical time

A significant result of the growth theory was the idea of a change in the flow of historical time - its acceleration, well known to historians and philosophers.

The change in the time scale that occurs as humanity grows can be easily represented mathematically if we refer to the instantaneous time of exponential growth T e = T 1 - T as a measure of change; then the growth is % per year. Since today we are very close to T1, then T e is simply equal to moving into the past. So 100 years ago T e =100 years, and the relative growth was equal to 1% per year. At the beginning of our era, 2 thousand years ago, growth was 0.05% per year, and 100 thousand years ago - 0.001% per year, i.e. it was so small that society was considered static. However, even then humanity grew proportionately, at the same relative pace as later, until the very beginning of the demographic transition in 1955.

The compression of system time is clearly visible if large historical periods are represented on a logarithmic grid. The table shows that the observations of anthropologists and the traditional ideas of historians clearly outline the boundaries of eras, evenly dividing the time on a logarithmic scale from T 0 = 4-5 million years ago to T 1 = 2000. After each cycle, the time remaining until the critical date , half the cycle duration. Thus, the Lower Paleolithic lasted a million years and ended half a million years ago, and the Middle Ages lasted a thousand years and ended 500 years ago. The very duration of demographic cycles varied from one million to 45 years and during each of l n K = 11 periods, 9 billion people lived. In this view, the Neolithic is in the middle of the development path (Table 1).

The acceleration of the historical process also occurs in relation to major historical phenomena. Thus, according to the historian Gibbon, the decline and decay of the Roman Empire lasted 1.5 thousand years, while current empires are created over centuries and disintegrate over decades. The transformation of historical system time is associated with the idea of longue dur?e as the concept of temporal extension in the French New Historical Science. The geometric reduction in the duration of historical periods as we approach our time is discussed by the St. Petersburg historian I.M. Dyakonov in the review "Paths of History. From Ancient Man to the Present Day."

Since the time of Hegel, following the eschatological tradition of the West, historians have proclaimed the end of History. The East perceived time as a cyclically repeating endless series of events, a sequence of reincarnations. However, the model combines both ideas about historical time. Moreover, the acceleration of the systemic development time is marked by a sequence of structural transformations, which physicists call phase transitions, of which the main one is the demographic transition.

Thus, the outlined approach made it possible to cover the entire development of humanity, considering the growth of its numbers as a process of self-organization. This became possible due to the transition to the next level of integration compared to that accepted in demography, when traditional demography methods were used to describe the behavior of an individual country or region on a time scale of one or two generations. In the presented periodization, without even turning to the formal conclusions of the modeling, it is clear how when the limit of compression of historical time is reached, an entire era of growth ends and, as a consequence, a change in the development paradigm occurs. After the demographic transition, humanity will enter a new era of its development with a new structure of time and zero or little numerical growth.

Demographic imperative

Following the demographer Landry, who discovered the demographic transition using the example of France, it is fair to believe that the period from the middle of the 18th century to the end of the 21st century should be called the era demographic revolution. We see that it represents the most significant event in human history since the appearance of our distant ancestors 1-2 million years ago. Then, in the process of the evolution of life on Earth, Homo sapiens appeared. Now we have approached the limit of the resources of his mind, but not the resources of his material existence.

Growth, described by cooperative interaction, including all types of human activity, essentially takes into account the development of science and technology as a systemic factor - a development that does not fundamentally distinguish our time in comparison with the past. Taking the law of development unchanged, as can be seen from the invariance of the quadratic growth of the world population before the demographic revolution, it should be assumed that it is not the depletion of resources, overpopulation or the development of science and medicine that will determine the change in the growth algorithm. Therefore, we must look for another reason for the change and limitation of population reproduction, as the main function of society.

Its change is determined not by external conditions, but by internal reasons, primarily by limiting the rate of growth, determined by the nature of the human mind and quantitatively expressed in the time spent on its formation. The influence of external, global conditions can only be felt in the next approximation, that is, when human activity becomes a planetary factor in the co-evolution of the biosphere and humanity. This significant conclusion is in conflict with traditional Malthusian ideas about the resource limitation of growth. As a result, in contrast to Malthus’s population principle, the principle should be formulated information demographic imperative.

Consequences of the demographic transition

Man has always had sufficient resources for further development, mastered them, settling throughout the Earth, and increased production efficiency. Until now and, apparently, in the foreseeable future, such resources will be available and will allow humanity to go through a demographic transition in which the population will no more than double. During this period, when contacts, resources and space were insufficient, local development ended, but on average overall growth was steady. Hunger in many regions is not associated with a general lack of food, but with methods of its distribution, which are of social and economic, rather than global resource origin.

Synergetics shows how the sustainability of overall growth is associated with rapid internal, civilizational processes of history, which have a smaller scale and stability than the main development covered by global interaction. Currently, a loss of systemic stability is possible when developing countries go through a demographic transition in a situation similar to that in which Europe found itself at the beginning of the twentieth century. During the World Wars, total population losses reached 250 million, an average of 12 thousand per day for 40 years. The transition is now happening twice as fast and reaching ten times as many people as it did in Europe then. The situation is that over the past fifteen years, China's economy has been growing at more than 10% per year, while its population of more than 1.2 billion is growing at 1.1%. India's population has crossed the billion mark and is growing by 1.9%, and the economy by 6% per year. Along with similar figures characterizing the rapid development of countries in the Asia-Pacific region, ever-increasing gradients of population growth and economic inequality are emerging. The presence of nuclear weapons in this region can both maintain the balance and threaten global security.

The demographic factor undoubtedly manifests itself in Muslim countries, where the rapid emergence of masses of restless youth in the process of urbanization destabilizes society. Moreover, for cultural reasons, Islam contributes little to economic cooperation, so the resulting “clash of civilizations” is associated not so much with the religious factor, but with the lag in the development of some Islamic countries.

Thus, the increasing unevenness of development can cause a loss of growth sustainability and, as a consequence, lead to wars. Such imbalances cannot be predicted, but indicating their likelihood is not only possible, but also necessary. It is precisely in maintaining the stability of development in an era of drastic changes that the main task of the world community lies. Without this, it is impossible to solve any other global problems, no matter how significant they may seem. Therefore, when discussing security issues, along with military, economic and environmental security, the demographic factor of world security and stability should be taken into account, which should take into account not only the quantitative parameters of population growth, but also qualitative, including ethnic, factors.

A paradoxical consequence of the demographic transition in developed countries is that families with an income of $100 a day have 1.15 children per woman. At the same time, in developing countries, families with an income of $2 a day have 5-6 children. Thus, modern developed society is demographically untenable. Under such conditions, it is impossible to stabilize the population of developed countries after the demographic transition without restoring the birth rate to the level of 2.1 children per woman and changing the values that guide society. Otherwise, the indigenous population of these countries will be displaced by emigrants with a high birth rate. Massive migration is already leading to contradictions that are evident in the modern world. This issue was recently examined by the famous American historian Patrick Buchanan in the book "The Death of the West: How Dying Populations and Invasive Emigrants Threaten Our Country and Civilization."

Economic aspect of demography

The proposed model considers the world population as a single self-organizing system. This allows us to cover a huge range of time and a range of phenomena, which includes essentially the entire history of mankind. The model offers a phenomenological, macroscopic description of phenomena, which is based on the idea of cooperative interaction, including all processes of a cultural, economic, technological, social and biological nature, leading to self-accelerated hyperbolic growth. This collective interaction is associated with consciousness, which in principle distinguishes humanity from the animal kingdom. It is expressed in culture as a factor in the development and transmission of information occurring between generations, as well as in its distribution throughout the ecumene. The latter circumstance leads to the synchronization of global development observed throughout the history and prehistory of mankind.

On the scale of global history, which Braudel called total history, development is stable and deterministic. And only as the spatial and temporal scale decreases, chaos sets in (as it is understood in synergetics and observed in history), which makes such processes unpredictable. Currently, it is non-equilibrium processes that lead not only to overall growth, but also to uneven development, an increase in the gap between wealth and poverty, which is so characteristic of the transitional era experienced by humanity.

These ideas are important for understanding global development from an economic perspective. Neoclassical economics considers linear models of reversible exchange and slow growth. This economic model of Walras is based on an analogy with thermodynamics, with its principle of detailed equilibrium and additive conservation laws. In the nonlinear model of quadratic growth, non-equilibrium and irreversible, information is not only not preserved, but is multiplied throughout the development of mankind. Moreover, the nonlinear model is not reducible to a linear one and, requiring a fundamentally different justification, acquires special significance for understanding the process of unbalanced development of humanity throughout history. Such ideas, associated with the generalization of the ideas of Max Weber and Joseph Schumpeter, underlie the evolutionary economics and economics of knowledge, which V.L. spoke about at the General Meeting of the Russian Academy of Sciences in 2002. Makarov. In this regard, it is worth paying attention to the symptomatic remark of the American publicist Francis Fukuyama: “Failure to understand that the foundations of economic behavior lie in the area of consciousness and culture leads to the widespread misconception in which material causes are attributed to those phenomena in society that, by their nature, are mainly belong to the realm of the spirit."

During the transition, labor productivity in industry and agriculture increases significantly, with 4% of the population feeding the entire country, and the service sector employs up to 80% of the workforce. An increase in the number of urban residents leads to changes in family structure, criteria for growth and success, priorities and values of society. Changes occur so rapidly that neither individuals, nor society as a whole, nor its institutions have time to adapt to new circumstances. Due to the short horizon of foresight, the collapse of socially-oriented planning principles in the economy occurs, and the dominance of the market element leads to the thoughtless development of a consumer society, and, as a result, to neglect of the environment.

A significant and general result of the demographic revolution will be an increase in life expectancy and a decrease in the birth rate, as a result of which the number of elderly people will increase and there will be fewer young people. In particular, this will lead to a decrease in demographic reserves for creating mass armies in developed countries. On the other hand, the burden on the health care and social security systems for pensioners will increase. Thus, in the foreseeable future, with a constant world population and its significant aging, two development alternatives are possible - either stagnation or even decline, or an increase in the quality of life.

The latter depends entirely on the development of culture, science and education. In developed countries, the time devoted to education is constantly increasing, a system of continuous education is developing - live and learn, while the birth rate is falling catastrophically - this is how the cultural factor limits the birth rate. This dilemma faces modern Russia (as well as all developed humanity) with particular acuteness. Thus, the transition after the demographic revolution to a new development paradigm will lead to profound changes in the historical process and its anticipation should attract the attention of everyone who seriously thinks about the fate of the world.

Look into the future

We first proposed quantitative theory of historical process. Demographic and temporal analysis of world development provides a global perspective of vision - a picture that can be considered metahistorical, located above history in breadth and time of coverage. As a phenomenological description, it does not address the details of those specific mechanisms in which we habitually seek explanations for the events of fast-moving life. Therefore, this methodology may seem abstract and even mechanistic to some. However, the generalizations obtained as a result of applying this approach provide a fairly complete and objective picture of the real world.

The development of humanity is based on the ability of the intellect to receive, comprehend and transmit information and ideas about the world around us, including the world of man himself. If evolution led to the emergence of consciousness, then today collective consciousness itself can become a new factor in the evolution of man and society. This is what determines the place and importance of science in the modern world. At the same time, our time has become critical, since explosive growth suddenly ended with a transition to a new stage of development and acutely raised the question of understanding the present and managing future development, no longer associated with numerical growth. Therefore, a comprehensive research program is needed that will allow the results obtained to be applied in various areas of the social sciences and, if possible, to implement them in life.

It is difficult to imagine that in the foreseeable future and in the absence of proper global political will, we will be able to consciously influence the global growth process, both due to the scale of what is happening and the pace of development of events, the very understanding of which is not yet complete. But at the same time, the proposed ideas contribute to the understanding and development of a general perspective of human development, “suitable” for history and economics, anthropology and demography. If doctors and politicians consider the systemic preconditions of the current transitional historical period as a source of stress for an individual and a critical condition for the world community, then the goals of the presented experience of interdisciplinary research will be achieved.

1 - Kapitsa S.P., General theory of world population growth. "Science", M. 1999.

2 - See Savelyeva I.M. and Poletaev A.V., History and time. In search of the lost. M. "Languages of Russian culture". 1997. A special issue of the journal “In the World of Science” No. 12 for 2003 was devoted to these issues.

Famous Russian scientist S.P. Kapitsa presented his version of the causes of the demographic crisis.

On October 20–21, the All-Russian Scientific Conference “Russian National Identity and the Demographic Crisis” was held in Moscow. The main organizer of the conference was the Center for Problem Analysis and Public Management Design (CPA GUP). Famous scientists and government officials made presentations, for example: S.S. Sulakshin, V.I. Yakunin, S.P. Kapitsa, V.E. Bagdasaryan and others. “TsPA State Unitary Enterprise” intends to publish a collection of articles based on the results of the conference. And with the report of the famous Russian scientist S.P. Kapitsa, with the permission of the Central Administration of the State Unitary Enterprise, we invite readers of “Russian Civilization” to familiarize themselves.

The global demographic crisis and Russia

Humanity is experiencing an era of global demographic revolution. A time when, after explosive growth, the world's population suddenly switches to limited reproduction and abruptly changes the nature of its development. This greatest event in the history of mankind since its inception is primarily manifested in population dynamics. However, it affects all aspects of the lives of billions of people, and that is why demographic processes have become the most important global problem in the world and in Russia. Not only the present, but also the foreseeable future, development priorities and sustainable growth depend on their fundamental understanding.

The phenomenon of demographic transition, when expanded reproduction of the population is replaced by limited reproduction and stabilization of the population, was discovered for France by demographer A. Landry. Studying this critical era of population development, he rightly believed that in terms of the depth and significance of its consequences it should be considered a revolution. However, demographers limited their research to the population dynamics of individual countries and saw their task as explaining what was happening through specific social and economic conditions. This approach made it possible to formulate recommendations for demographic policy, but in this way it excluded understanding of the broader, global aspects of this problem. Consideration of the world population as a whole, as a system, was denied in demography, since with this approach it was impossible to determine the reasons for the transition common to humanity. Only by rising to the global level of analysis, changing the scale of the problem, and considering all the world's populations as a single object, as a system, was it possible to describe the global demographic transition from the most general positions. Such a generalized understanding of history turned out to be not only possible, but also very effective. To do this, it was necessary to radically change the method of research, the point of view, both in space and time, and consider humanity from the very beginning of its appearance as a global structure. It should be emphasized that most major historians, such as Fernand Braudel, Karl Jaspers, Immanuel Wallerstein, Nikolai Conrad, Igor Dyakonov, argued that a significant understanding of human development is possible only at the global level. It is in our era, when globalization has become a sign of the times, that this approach opens up new opportunities in the analysis of both the current state of the world community, growth factors in the past, and development paths in the foreseeable future.

The Club of Rome was the first to put global issues on the agenda 30 years ago. These studies relied on the analysis of extensive databases and computer modeling of the processes that, according to the authors, determined growth and development. However, the club’s first report, “The Limits to Growth,” was deeply criticized, and the main conclusion that the limits of human growth are determined by resources turned out to be untenable. To understand the difficulties of direct mathematical modeling, consider the insightful remark of Nobel Prize-winning American economist Herbert Simon: “Forty years of experience modeling complex systems on computers that grew bigger and faster every year has taught us that brute force will not lead us down the royal path.” to understanding such systems... Thus, modeling will require an appeal to the basic principles that will lead to the resolution of this paradox of complexity.” Thus, it was then that global problems were highlighted, to which we have now returned at a new level of understanding and development of mathematical modeling methods.

Mathematical model of population growth

Until the turn of 2000, the population of our planet was growing at an ever-increasing rate. At that time, it seemed to many that a population explosion, overpopulation and the inevitable depletion of natural resources and reserves would lead humanity to disaster. However, in 2000, when the world population reached 6 billion and the population growth rate peaked at 87 million per year or 240 thousand people per day, the growth rate began to decrease. Moreover, both the calculations of demographers and the general theory of population growth on Earth indicate that in the very near future, growth will practically cease. Thus, the population of our planet, as a first approximation, will stabilize at the level of 10 - 12 billion and will not even double compared to what it already is. The transition from explosive growth to stabilization occurs in a historically insignificantly short period of time - less than a hundred years, and this will complete the global demographic transition.

As a result, it turned out that it is the nonlinear dynamics of human population growth, subject to our own internal forces, that determines our development and its limit. This allows us to formulate the phenomenological principle of the demographic imperative, in contrast to Malthus’s population principle, where resources determine the limits of growth.

Until very recently, the sudden appearance of man was a mystery, since there were no intermediate stages preceding our appearance as a species. However, the discovery of the HAR-1F gene has recently been reported. This RNA gene controls brain development during the first 7 to 19 weeks of embryonic development. A mutation of this gene led 7 to 5 million years ago to the fact that the human brain was able to suddenly grow. It is in this that one should see the reason for the emergence of a qualitatively higher level of intelligence, which opened the way for the subsequent development of humanity, which is described by the model developed below.

Thus, human ancestors arose among the apes and appeared in Africa millions of years ago. Then, after a long era of anthropogeny (A), they began to speak, mastered fire and the technology of stone tools. The number of our most ancient ancestors was about one hundred thousand, and people had already begun to spread throughout the globe. Since then, the process of our development has remained unchanged and that is why its understanding is so significant for us today, when the number of people has increased another hundred thousand times - to modern billions. Not a single species of animal comparable to us has ever developed like this: for example, even now about one hundred thousand bears or wolves live in Russia, and the same number of large monkeys live in tropical countries. Only domestic animals have multiplied their numbers far beyond their wild counterparts: number in the world

In order to explain the essence of the problem, let us turn to how humanity has grown in number and developed over the past 4 thousand years. The starting point was the fact that the growth of the Earth's population is subject to a surprisingly simple and universal pattern of hyperbolic growth. Where the population is presented on a logarithmic scale, and the passage of time is presented on a linear scale, which indicates the main periods of world history. If the world's population grew exponentially, then such growth would be shown schematically on a straight line graph. Therefore, this representation of growth is widely used in statistics and economics when they want to show that growth occurs according to the law of compound interest.

The secret of hyperbolic, explosive development is that the rate of its growth is proportional not to the first power of the population, as in the case of exponential growth, but to the second power - to the square of the world population, as a measure of development. It was the analysis of the hyperbolic growth of mankind, connecting the number and growth of mankind with its development and the measure of which is the square of the world population, which made it possible to understand in a new way all the specifics of the history of mankind and to propose a general collective mechanism of development based on the dissemination and reproduction of information. Such quadratic growth is well studied in physics, and it manifests itself when development occurs due to the collective interaction that arises in a dynamic system, when all its components intensively interact with each other. As an instructive example of such processes, let us cite an atomic bomb, in which a nuclear explosion occurs as a result of a branched chain reaction. The quadratic growth of the population of our planet indicates that a similar process is occurring with humanity - only much slower, but no less dramatic. If exponential growth is determined by a person’s individual ability to reproduce, then the explosive development of humanity is a collective process, occurring throughout society and covering the entire world.

Thus, a growth rate proportional to the square of the world population indicates a collective and cooperative interaction responsible for growth. Slow at the beginning, development accelerates, and as we approach the year 2000. it rushes into the infinity of the population explosion. The task of the theory and model of hyperbolic growth is to establish the limits of applicability of this time-averaged asymptotic growth formula. These limits are determined by the fact that the asymptotic expressions, due to the self-similarity of growth, do not depend on the local time scale of development associated with the effective life expectancy of a person. Taking into account this time, equal to 45 years, determines both the moment of the beginning of human history 4 - 5 million years ago, and the passage of the world population through the peak of the global demographic transition in 2000. As a result, in elementary terms, but based on the statistical principles of theoretical physics, it was possible to describe the dynamically self-similar development of humanity over more than a million years - from the emergence of man to our time and the onset of the demographic transition. Thanks to averaging, this interaction is not local and has a memory of the past, and therefore global growth is expressed through the instantaneous value of the Earth's population. Despite the simplicity of the model, it points to the stability of deterministic global growth, which is stabilized by the rapid and chaotic disturbances of current history. These mechanisms are well studied in the nonlinear theory of large systems. Thus, based on the model, it is possible to estimate the total number of people who have ever lived on Earth - about 100 billion, the number of main periods of development, assess the sustainability of growth and obtain a number of other results on the nature of the demographic revolution. We emphasize that there is every reason to believe that the quadratic interaction responsible for growth is due to the exchange and dissemination of generalized information. It spreads through a chain reaction and multiplies irreversibly at every stage of development, and humanity from the very beginning, for a million years now, has been an information community.

Growth of the Earth's population and time in History

The ancient world lasted about three thousand years, the Middle Ages - a thousand years, the Modern Age - three hundred years, and Recent history - just over a hundred years. Historians have long paid attention to this contraction of historical time, but to understand the compaction of time, it must be compared with the dynamics of population growth. Unlike the usual exponential growth, when the relative growth rate is constant and the population multiplies over a certain time, for hyperbolic growth the multiplication time is proportional to the antiquity, calculated from the critical year 2000. Thus, 2000 years ago the population grew by 0.05% per year, 200 years ago - by 0.5% per year, and 100 years ago - by 1% per year. Humanity reached a maximum relative growth rate of 2% in 1960. - 40 years earlier than the maximum absolute growth of the world population. Thus, during each of the 11 periods of development from the Lower Paleolithic to the demographic revolution, 9 billion people lived. If the duration of the Lower Paleolithic was one million years, then the last period of the global demographic transition lasted only 45 years.

It can be shown that such accelerated development leads to the fact that after each period, all remaining development takes place in a time equal to half the duration of the previous stage. So, after the Lower Paleolithic, which lasted a million years, half a million years remain until our time; after the millennium of the Middle Ages, 500 years remain. These stages of development, identified by anthropologists and historians, occur synchronously throughout the world, when all peoples are covered by a common information process. The compression of the time of historical development is also visible in how the speed of the historical process increases as it approaches our time. If the history of Ancient Egypt and China took thousands of years and is counted in dynasties, then the pace of the history of Europe was determined by individual reigns. If the Roman Empire collapsed within a thousand years, then modern empires disappeared within decades, and in the case of the Soviet Empire, even faster. Thus, in the last era of the demographic revolution, the acceleration of the historical process reached its limit before the era (C) of stabilization of the population growth of our planet.

The onset of the Neolithic, when there was a concentration of population in villages and cities, appears exactly in the middle of the era of explosive development (B), represented in logarithmically transformed time. The demographic revolution appears as a strong phase transition, when, due to the instability of the explosive growth of humanity in an aggravated regime, a change in the growth rate and a fundamental change in the development paradigm itself occur. Thus, at the moment of the demographic explosion, as in a shock wave, the internal time of history, the intrinsic duration of development, is reduced to the limit. This limit of time compression cannot be shorter than the effective life of a person, and that is why this is followed by a sharp turn in our development; if not the end of History, as stated by Francis Fukuyama, then a fundamental change in the rate of growth of mankind begins. History, naturally, will continue after the world population stops growing, but as a consequence of the demographic revolution and at a much calmer pace.

This is how the global growth of humanity appears if we analyze metahistory in the light of the development of the demographic system and the logarithmic transformation of time. The dynamic view of the course of historical time has long been discussed in historical science, but in the developed theory it acquires, as in the theory of relativity, a quantitative meaning when historical time is equal to the logarithm of physical, Newtonian time. In transformed time, historical processes appear uniform throughout the entire development, which expresses the dynamic self-similarity of growth, although the pace of development itself differs tens of thousands of times. Thus, as a result of time compression, the historical past turns out to be much closer to us than it seems at first glance at the number of generations and calendar time of past eras.

The driving factor of development is connections that embrace all of humanity in a single effective information field. This connection should be understood generally as customs, beliefs, ideas, skills and knowledge passed on from generation to generation during the training, education and upbringing of a person as a member of society. It is generalized information that determines the dynamics of social and economic processes. Global development invariably follows a trajectory of hyperbolic growth, which cannot be significantly disrupted by pandemics, world wars, or natural disasters. Naturally, there are ups and downs of growth, ways of life change, peoples migrate, fight and disappear, and the further into the past we look at the pace of development, the slower it happens. Then, during the life of man, circumstances and lifestyle changed little, despite the fluctuations and disturbances that always existed, including ice ages and climate changes greater than those that are so much talked about today. In the era of the demographic revolution, it is precisely the scale of significant social changes occurring during a person’s life that has become so significant that neither an individual nor society as a whole has time to adapt to the pace of changes in the world order - a person is “in a hurry to live and in a hurry to feel,” like never before.

Analysis shows that growth proportional to the square of the world population expresses the collective nature of the forces determining development. This connection has existed at all times, only in the past it took longer. Let us emphasize that this immutable law is applicable only for an integral closed system, such as the interconnected population of the world. As a result, global growth does not require migration to be taken into account, since it is an internal process of interaction through the movement of people, which does not directly affect their numbers, since our planet is still difficult to leave. This nonlinear law cannot be extended to a single country or region, but the development of each country should be considered against the backdrop of world population growth. A consequence of the non-locality of the quadratic growth law is the noted synchronization of the world historical process and the inevitable lag of isolates, which found themselves long separated from the bulk of humanity.

Global demographic revolution

1.Analysis of accompanying phenomena

When analyzing the phenomena accompanying the demographic revolution, one can follow two paths. Firstly, you can start from the specific observations of a historian or sociologist regarding significant social patterns from the country, and synthesize a general picture of development from the particulars. Or you can, based on the general concept, analyze specific phenomena. Obviously, both approaches are effective. However, the second, based on the general picture of development, allows us to achieve a more complete understanding of the ongoing changes at a general level and, on the basis of a new synthesis, to establish the fundamental primacy of the mechanism of the information process of growth. This is precisely what is important if we want to understand the meaning of this unique historical era that humanity is experiencing.

The population of developed countries has already stabilized at one billion. They went through the transition just 50 years before developing countries, and now in these countries we can see a series of phenomena that are gradually spreading to the rest of humanity. In Russia, many crisis phenomena, even in an intensified form, reflect the global crisis. Meanwhile, the transition in developing countries affects more than 5 billion people, whose numbers will double as the global demographic transition ends in the second half of the 21st century. This is happening twice as fast as in Europe. The speed of growth and development processes is striking in its intensity - for example, the Chinese economy is growing by more than 10% per year. Such changes and growth were occurring in Russia and Germany on the eve of the First World War and undoubtedly contributed to the crisis of the 20th century. Energy production in the countries of Southeast Asia is growing by 7–8% per year, and the Pacific Ocean is becoming the last Mediterranean on the planet after the Atlantic Ocean and the Mediterranean Sea.

2.Demographic situation on a global scale

Let's look at population calculations in the future, where the modeling results can be compared with calculations by the UN, the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA), and other agencies. The UN forecast is based on a generalization of a number of scenarios for fertility and mortality in 9 regions of the world and is extended to 2150. By this time, according to the UN optimal scenario, the Earth's population will reach a constant limit of 11 billion. 600 million. In the report of the UN Population Division in 2003, according to the average option, by 2300. 9 billion are expected. As a result, both demographers’ calculations and growth theory lead to the conclusion that after the transition, the Earth’s population will stabilize at 10–11 billion. The difference between the world population and the calculation data, which coincide before and after the World Wars, makes it possible to estimate the total losses of humanity during this period, amounting to 250 - 280 million people, which is more than the usually given figures. At present, the mobility of peoples, classes and people has increased exceptionally. Both the Asia-Pacific countries and other developing countries are affected by powerful migration processes. Population movements occur both within countries (primarily from villages to cities) and between countries. The growth of migration processes, which are now sweeping the whole world, leads to destabilization of both developing and developed countries, giving rise to a set of problems that require separate consideration. The dynamics of modern developed society undoubtedly create a stressful environment. This happens at the individual level when the bonds that lead to family formation and stability are broken down. One consequence of this was the sharp decline in the number of children per woman observed in developed countries. So, in Spain this number is 1.20; in Germany - 1.41; in Japan -1.37; in Russia - 1.21 and in Ukraine -1.09, while on average 2.15 children are needed to maintain simple reproduction of the population. Thus, all the richest and most economically developed countries, which went through the demographic transition 30–50 years earlier, turned out to be incompetent in their main function - population reproduction. This is facilitated by: a long period of education; liberal value system; the collapse of traditional ideologies in the modern world. If this trend continues, then the main population of developed countries is doomed to extinction and displacement by emigrants from more fertile ethnic groups. This is one of the strongest signals that demographics give us. If in the 19th and 20th centuries. During the peak of population growth in Europe, emigrants headed to the colonies, but now a reverse movement of peoples has arisen, significantly changing the ethnic composition of the metropolises. Let us note that a significant, and in many cases the overwhelming majority of migrants are illegal and, in essence, not under the control of the authorities.

Thus, if in developed countries we note a sharp decline in population growth, in which the population does not renew itself and is rapidly aging, then in the developing world the opposite picture is still observed - where the population, which is dominated by young people, is growing rapidly. The change in the ratio of older and younger people was the main result of the demographic revolution, and has now led to the maximum stratification of the world by age composition. It is the youth, which becomes more active in the era of the demographic revolution, that is a powerful driving force of historical development. The stability of the world largely depends on where these forces are directed. For Russia, such a region has become Central Asia - its “soft underbelly”, where the population explosion, the state of the economy and the water supply crisis have led to a tense situation in the very center of Eurasia. In the future, with the completion of the demographic revolution by the end of the 21st century, there will be a general aging of the world population. If at the same time the number of children among emigrants also decreases, becoming less than what is necessary for the reproduction of the population, this state of affairs can lead to a crisis in the development of humanity on a global scale. However, it can be assumed that the crisis of population reproduction itself was a reaction to the demographic revolution and therefore can be overcome in the foreseeable future.

3.Demographic revolution and crisis of ideologies

The demographic revolution is expressed not only in demographic processes, but also in the destruction of the connection of times, the collapse of consciousness and chaos, and in the moral crisis of society. This is clearly reflected in the manifestations, first of all, of mass culture, so irresponsibly disseminated by the media, in some trends in modern art and postmodernism in philosophy. Such a listing of critical phenomena is inevitably incomplete, but it is intended to draw attention to moments that, although of different scales, have common causes in the era of global demographic transition, when the discrepancy between consciousness and physical development potential has increased so much.

This crisis is global in nature, and its ultimate expression, undoubtedly, has become nuclear weapons and the excessive armament of some countries, the crisis of the concept: “you have strength, you don’t need intelligence.” The impotence of force was clearly demonstrated by the collapse of the Soviet Union, when, despite the enormous armed forces, it was ideology that turned out to be the “weak link.” However, along with this, new development goals arise, a search and change of values occurs, affecting the very foundations of ensuring sustainability and managing society as a knowledge society. When considering the mechanisms of growth and development of society, it should be noted that the model of information development describes a non-equilibrium growth process. It is fundamentally different from conventional models of economic growth, where the archetype is the thermodynamics of equilibrium systems in which slow, adiabatic development occurs, and the market mechanism contributes to the establishment of detailed economic equilibrium, when processes are in principle reversible and the concept of property corresponds to the laws of conservation. However, these ideas, at best, act locally and are not applicable when describing the irreversible global process of dissemination and multiplication of information that does not occur locally and therefore are not applicable when describing non-equilibrium development. Note that economists since the days of early Marx, Max Weber and Joseph Schumpeter have noted the influence of intangible factors in our development, as Francis Fukuyama recently stated: “Failure to understand that the foundations of economic behavior lie in the field of consciousness and culture leads to a common misconception, according to to which material causes are attributed to those phenomena in society which, by their nature, primarily belong to the realm of the spirit.”

Let's return to the crisis of ideologies and the system of moral norms and values that govern people's behavior. Such norms are formed and reinforced by tradition over a long period of time, and in an era of rapid change, this time simply does not exist. Thus, during the period of the demographic revolution in a number of countries, including Russia, there is a collapse of consciousness and management of society, erosion of power and management responsibility, organized crime and corruption are growing and, as a reaction to the unsettled life and underemployment of the population, the growth of alcoholism, drug addiction and suicide, leading to increased mortality among men. In developed countries, labor is moving from manufacturing to services. For example, in Germany in 1999. turnover in the information technology sector was greater than in the automobile industry, a pillar of the German economy. Along with this, there is a growth of marginal phenomena, a revision of established concepts without proper selection and critical analysis for the development of principles and criteria in culture and ideology, which are then enshrined in tradition and legislation.

On the other hand, the abstract and largely outdated concepts of some philosophers, theologians and sociologists that came from the past acquire the meaning, if not the sound, of political slogans. From here arises an irrepressible desire to “correct” history and apply it to our time, when the historical process, which previously took centuries, has now been extremely accelerated and which urgently requires a new understanding, and not hopes and searches for solutions in the past or submission to the blind pragmatism of current politics. Thus, the extreme compression of historical time leads to the fact that the time of virtual history has merged with the time of real politics.

Rapid growth is accompanied by manifestations of increasing disequilibrium in society and the economy in the distribution of labor results, information and resources, in the primacy of local self-organization over the organization, the market with its short horizon of vision compared to longer-term social priorities for the development of society and the decreasing role of the state in economic management. Along with the collapse of previous ideologies, the growth of self-organization and the development of civil society, old structures are being replaced by new ones in search of new connections, ideas and development goals that affect the foundations of management and sustainability of society.

The demographic factor, which is associated with the phase of the demographic transition, plays a significant role in the emergence of the danger of war and armed conflicts, primarily in developing countries. Moreover, the very phenomenon of terrorism expresses a state of social tension, as was already the case at the peak of the demographic transition in Europe in the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Note that a quantitative analysis of the sustainability of the development of the global demographic system indicates that the maximum instability of development may have already been passed. With the long-term stabilization of the population and a radical change in the historical process, one can expect a possible demilitarization of the world with a decrease in the demographic factor in strategic tension and the onset of a new time periodization of history. In defense policy, demographic resources limit the size of armies, which requires modernization of the armed forces. The importance of both technical equipment and the increasing role of what is commonly called psychological warfare techniques is increasing. This is why the role of ideology as the basis of politics is increasing, and because the dissemination of ideas through active propaganda, advertising and culture itself is becoming an increasingly important factor and instrument of modern politics. Thus, in developed countries that have completed the demographic transition, a change in priorities is already visible in defense, economics, education, healthcare, social insurance, policy and media practice.

4.Information nature of human development

We see that humanity since its inception, when it took the path of hyperbolic growth and has steadily developed as an information society. Only in the past did this happen gradually, and growth did not lead to tension and stress, so characteristic of our time. The analysis also shows that it was not resources and the environment, but the limited technology of their production and development that caused the demographic transition. The growth limitation that has come is due to the fact that the ideas necessary for using generalized information have largely been exhausted, and the training, education and upbringing of the next generation requires much more time than before. In other words, we are dealing not only with the explosive development of the information society, but also with its crisis. This is a paradoxical conclusion, but it leads to consequences that are of increasing importance for understanding the processes occurring during the passage through the critical era of the demographic revolution and assessments of the future that awaits us, and here the example of Europe is especially instructive.

Once the world's population has stabilized, development can no longer be linked to numerical growth, and therefore the path it will take must be discussed. Development may stop - and then a period of decline will begin, and the ideas of “The Decline of Europe” will be embodied (see, for example, “Children of the Dead” by Nobel Prize Laureate Elfriede Jelinek). But another, qualitative development is also possible, in which the meaning and goal will be the quality of a person and the quality of the population, and where human capital will be its basis. A number of authors point to this path. And the fact that Oswald Spengler's gloomy forecast for Europe has not yet come true gives hope that the path of development will be connected with knowledge, culture and science. It is the new Europe, many of whose countries were the first to go through the demographic transition, that is now boldly paving the way for the reorganization of its economic, political and scientific space, and indicating the processes that other countries can expect. This critical bifurcation, the choice of development path, faces Russia with all its severity.

Nowadays, all of humanity is experiencing an extraordinary growth in information technology, primarily the widespread spread of network communications, when one third of humanity already owns mobile phones. Finally, the Internet has become an effective mechanism for collective information network interaction, even the materialization of collective memory, if not the very consciousness of humanity, realized at the technological level. These opportunities make new demands on education, when not knowledge, but its understanding becomes the main task of educating the mind and consciousness: Vaclav Havel noted that “the more I know, the less I understand.” But simple application of knowledge does not require deep understanding, which has led to pragmatic simplification and reduction of requirements in the process of mass training. Currently, the duration of education is increasing and often the most creative years of a person, including the years most suitable for starting a family, are spent studying. The increasing responsibility to society in the formation of values, in the presentation of education and knowledge, must be recognized by the media. It is not without reason that some analysts define our era as a time of excessive information load, due to advertising, propaganda and entertainment, as a burden of deliberate consumption of information, for which the media bear no small responsibility. Back in 1965 outstanding Soviet psychologist A.N. Leontyev astutely noted that “an excess of information leads to impoverishment of the soul.”

Naturally, awareness of the information nature of human development attaches special importance to the achievements of science, and in the post-industrial era its importance only increases. Unlike “world” religions, from the very emergence of fundamental scientific knowledge, science has developed as a global phenomenon in world culture. If at the beginning its language was Latin, then French and German, now English has become the language of science. However, the largest growth in the number of scientific workers is currently occurring in China. If we can expect a new breakthrough in world science from Chinese scientists and those who were educated in the USA, Europe and Russia, then in India the export of software products in 2004 amounted to $25 billion, already showing a new example of the international division of labor. In the era of the demographic revolution, with a general increase in production, education and population mobility, economic inequality is also growing - both within developing countries and regionally. On the other hand, in response to the challenge of the demographic imperative, the political processes that govern and stabilize development do not keep pace with economic growth.

Russia in the global demographic context

The demographic situation in Russia is discussed in detail in a collection published under the editorship of A. G. Vishnevsky. Considering the demography of Russia in a global context, we should dwell on three issues, which, in particular, are highlighted in the latest Address of President V.V. Putin to the 2006 Federal Assembly. In the first place, the President highlighted the birth rate crisis, which is determined by the fact that on average there are 1.3 children per woman. With this level of birth rate, the country cannot even maintain the size of its population, which is currently decreasing by 700,000 people annually in Russia. However, low birth rates, as we have seen, are a characteristic feature of all modern developed countries, to which Russia undoubtedly belongs. Therefore, we can believe that this reflects a general crisis, the causes of which lie not only and not so much in material factors, but in the culture and moral state of society. In Russia, of course, material factors and wealth stratification play a significant role, so the proposed measures will help correct the high degree of unevenness in income distribution in our country. However, no less and even a major role belongs to the moral crisis that has emerged in the modern developed world, the crisis of the value system. Unfortunately, in education policy and especially in the media, we completely thoughtlessly import and even propagate ideas that only worsen the situation with the crisis of identity. This is also facilitated by the social position of part of the intelligentsia, who, having received freedom, imagined that this frees them from responsibility to society at such a critical moment in the history of the country and the world.

For Russia, a significant factor is migration, which accounts for up to half of the population increase. Moreover, the working class is also replenished, and with the return of native Russians to their homeland, the country receives people enriched by the experience of other cultures. No less significant is the influx of migrants from indigenous nationalities from neighboring countries, mainly for economic reasons. Thus, migration has become a new and very dynamic phenomenon in the demography of Russia, and one can only note that, as in other countries, in the Russian context many problems are of a similar nature. Thus, in the United States, most new emigrants do not have legal status. In France, the question of the assimilation of emigrants led to their isolation and major unrest. In other words, in this area, the mobility of peoples that has arisen in the modern world within the framework of Russian reality has manifested itself in a similar way. However, in one thing Russia stands out among all developed countries: high mortality among men. The average life expectancy of men in Russia is 58 years - 20 years less than in Japan. The reason for this is, among other things, the sad state of our medicine, or rather the healthcare system, which, undoubtedly, was aggravated by the thoughtless monetarist approach to organizing this area of social protection of citizens, including the inadequacy of pensions. The role of moral factors, the decline in the value of human life in the public consciousness, the growth of alcoholism in the most dangerous forms, smoking and the inability to adapt to new socio-economic conditions are also great here. The consequence of these factors was the disintegration of the family, a catastrophic for the history of Russia increase in the number of street children, which assumed epidemic proportions.

The listed factors are interconnected, as in any complex system, and therefore identifying the main causes of the crisis presents great methodological difficulties. One thing is clear: the world is going through an era of crisis, the scale of which is incomparable to any collisions and catastrophes of the past. That is why the current crisis in Russia is not only the result of its history, but also to a large extent a reflection, or rather a refraction, in our country of the global crisis of the demographic revolution. Moreover, in its history, Russia has reflected many aspects of global history, and therefore it sometimes seems to us that our path is special. But we simply represent a model of the world by our geography, ethnic composition, and religious diversity, and that is why the analysis of global problems is so important for us. Therefore, the history of individual countries has limited meaning for Russia, and this difference in time and space scales, ethnic and historical diversity should be taken into account when we turn to the experience of others.

Conclusion